Price Oracle

The final mechanism we’re going to add to our DEX is a price oracle. Even though it’s not essential to a DEX (some DEXes don’t implement a price oracle), it’s still an important feature of Uniswap and something interesting to learn about.

What is Price Oracle?

A price oracle is a mechanism that provides asset prices to the blockchain. Since blockchains are isolated ecosystems, there’s no direct way of querying external data, e.g. fetching asset prices from centralized exchanges via API. Another, a very hard one, problem is data validity and authenticity: when fetching prices from an exchange, how do you know they’re real? You have to trust the source. But the internet is not often secure and, sometimes, prices can be manipulated, DNS records can be hijacked, API servers can go down, etc. All these difficulties need to be addressed so we can have reliable and correct on-chain prices.

One of the first working solutions to the above-mentioned problems was Chainlink. Chainlink runs a decentralized network of oracles that fetch asset prices from centralized exchanges via APIs, average them, and provide them on-chain in a tamper-proof way. Chainlink is a set of contracts with one state variable, asset price, that can be read by anyone (any other contract or user) but can be written only by oracles.

This is one way of looking at price oracles. There’s another.

If we have native on-chain exchanges, why would we need to fetch prices from outside? This is how the Uniswap price oracle works. Thanks to arbitraging and high liquidity, asset prices on Uniswap are close to those on centralized exchanges. So, instead of using centralized exchanges as the source of truth for asset prices, we can use Uniswap, and we don’t need to solve the problems related to delivering data on-chain (we also don’t need to trust data providers).

How Uniswap Price Oracle Works

Uniswap simply keeps a record of all previous swap prices. That’s it. But instead of tracking actual prices, Uniswap tracks the accumulated price, which is the sum of prices at each second in the history of a pool contract.

This approach allows us to find time-weighted average price between two points in time ( and ) by simply getting the accumulated prices at these points ( and ), subtracting one from the other, and dividing by the number of seconds between the two points:

This is how it worked in Uniswap V2. In V3, it’s slightly different. The accumulated price is the current tick (which is of the price):

And instead of averaging prices, geometric mean is taken:

To find the time-weighted geometric mean price between two points in time, we take the accumulated values at these time points, subtract one from the other, divide by the number of seconds between the two points, and calculate :

Uniswap V2 didn’t store historical accumulated prices, which required referring to a third-party blockchain data indexing service to find a historical price when calculating an average one. Uniswap V3, on the other hand, allows to store up to 65,535 historical accumulated prices, which makes it much easier to calculate any historical time-weighted geometric price.

Price Manipulation Mitigation

Another important topic is price manipulation and how it’s mitigated in Uniswap.

It’s theoretically possible to manipulate a pool’s price to your advantage: for example, buy a big amount of tokens to raise its price and get a profit on a third-party DeFi service that uses Uniswap price oracles, then trade the tokens back to the real price. To mitigate such attacks, Uniswap tracks prices at the end of a block, after the last trade of a block. This removes the possibility of in-block price manipulations.

Technically, prices in the Uniswap oracle are updated at the beginning of each block, and each price is calculated before the first swap in a block.

Price Oracle Implementation

Alright, let’s get to code.

Observations and Cardinality

We’ll begin by creating the Oracle library contract and the Observation structure:

// src/lib/Oracle.sol

library Oracle {

struct Observation {

uint32 timestamp;

int56 tickCumulative;

bool initialized;

}

...

}

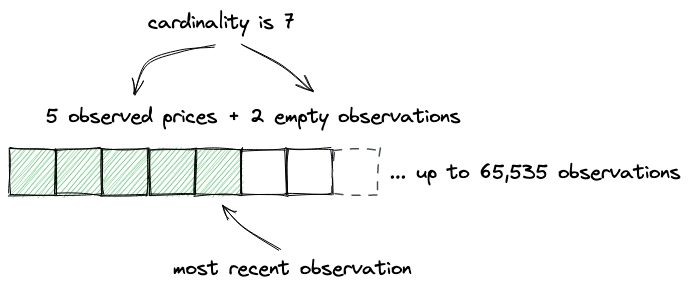

An observation is a slot that stores a recorded price. It stores a price, the timestamp when this price was recorded, and the initialized flag that is set to true when the observation is activated (not all observations are activated by default). A pool contract can store up to 65,535 observations:

// src/UniswapV3Pool.sol

contract UniswapV3Pool is IUniswapV3Pool {

using Oracle for Oracle.Observation[65535];

...

Oracle.Observation[65535] public observations;

}

However, since storing that many instances of Observation requires a lot of gas (someone would have to pay for writing each of them to the contract’s storage), a pool by default can store only 1 observation, which gets overwritten each time a new price is recorded. The number of activated observations, the cardinality of observations, can be increased at any time by anyone willing to pay for that. To manage cardinality, we need a few extra state variables:

...

struct Slot0 {

// Current sqrt(P)

uint160 sqrtPriceX96;

// Current tick

int24 tick;

// Most recent observation index

uint16 observationIndex;

// Maximum number of observations

uint16 observationCardinality;

// Next maximum number of observations

uint16 observationCardinalityNext;

}

...

observationIndextracks the index of the most recent observation;observationCardinalitytracks the number of activated observations;observationCardinalityNexttracks the next cardinality the array of observations can expand to.

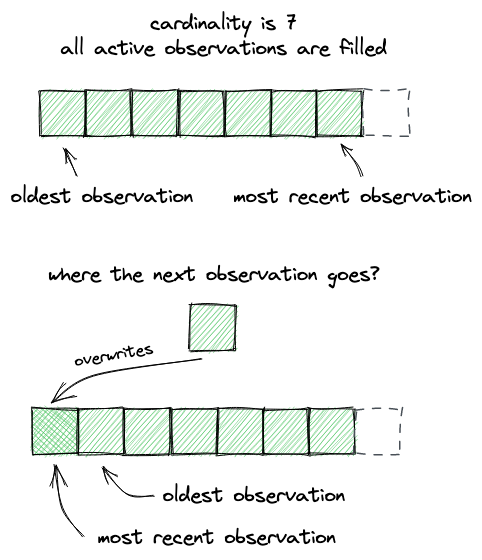

Observations are stored in a fixed-length array that expands when a new observation is saved and observationCardinalityNext is greater than observationCardinality (which signals that cardinality can be expanded). If the array cannot be expanded (the next cardinality value equals the current one), the oldest observations get overwritten, i.e. observation is stored at index 0, the next one is stored at index 1, and so on.

When a pool is created, observationCardinality and observationCardinalityNext are set to 1:

// src/UniswapV3Pool.sol

contract UniswapV3Pool is IUniswapV3Pool {

function initialize(uint160 sqrtPriceX96) public {

...

(uint16 cardinality, uint16 cardinalityNext) = observations.initialize(

_blockTimestamp()

);

slot0 = Slot0({

sqrtPriceX96: sqrtPriceX96,

tick: tick,

observationIndex: 0,

observationCardinality: cardinality,

observationCardinalityNext: cardinalityNext

});

}

}

// src/lib/Oracle.sol

library Oracle {

...

function initialize(Observation[65535] storage self, uint32 time)

internal

returns (uint16 cardinality, uint16 cardinalityNext)

{

self[0] = Observation({

timestamp: time,

tickCumulative: 0,

initialized: true

});

cardinality = 1;

cardinalityNext = 1;

}

...

}

Writing Observations

In the swap function, when the current price is changed, an observation is written to the observations array:

// src/UniswapV3Pool.sol

contract UniswapV3Pool is IUniswapV3Pool {

function swap(...) public returns (...) {

...

if (state.tick != slot0_.tick) {

(

uint16 observationIndex,

uint16 observationCardinality

) = observations.write(

slot0_.observationIndex,

_blockTimestamp(),

slot0_.tick,

slot0_.observationCardinality,

slot0_.observationCardinalityNext

);

(

slot0.sqrtPriceX96,

slot0.tick,

slot0.observationIndex,

slot0.observationCardinality

) = (

state.sqrtPriceX96,

state.tick,

observationIndex,

observationCardinality

);

}

...

}

}

Notice that the tick that’s observed here is slot0_.tick (not state.tick), i.e. the price before the swap! It’s updated with a new price in the next statement. This is the price manipulation mitigation we discussed earlier: Uniswap tracks prices before the first trade in the block and after the last trade in the previous block.

Also notice that each observation is identified by _blockTimestamp(), i.e. the current block timestamp. This means that if there’s already an observation for the current block, a price is not recorded. If there are no observations for the current block (i.e. this is the first swap in the block), a price is recorded. This is part of the price manipulation mitigation mechanism.

// src/lib/Oracle.sol

function write(

Observation[65535] storage self,

uint16 index,

uint32 timestamp,

int24 tick,

uint16 cardinality,

uint16 cardinalityNext

) internal returns (uint16 indexUpdated, uint16 cardinalityUpdated) {

Observation memory last = self[index];

if (last.timestamp == timestamp) return (index, cardinality);

if (cardinalityNext > cardinality && index == (cardinality - 1)) {

cardinalityUpdated = cardinalityNext;

} else {

cardinalityUpdated = cardinality;

}

indexUpdated = (index + 1) % cardinalityUpdated;

self[indexUpdated] = transform(last, timestamp, tick);

}

Here we see that an observation is skipped when there’s already an observation made at the current block. If there’s no such observation though, we’re saving a new one and trying to expand the cardinality when possible. The modulo operator (%) ensures that the observation index stays within the range and resets to 0 when the upper bound is reached.

Now, let’s look at the transform function:

function transform(

Observation memory last,

uint32 timestamp,

int24 tick

) internal pure returns (Observation memory) {

uint56 delta = timestamp - last.timestamp;

return

Observation({

timestamp: timestamp,

tickCumulative: last.tickCumulative +

int56(tick) *

int56(delta),

initialized: true

});

}

What we’re calculating here is the accumulated price: the current tick gets multiplied by the number of seconds since the last observation and gets added to the last accumulated price.

Increasing Cardinality

Let’s now see how cardinality is expanded.

Anyone at any time can increase the cardinality of observations of a pool and pay for the gas required to do so. For this, we’ll add a new public function to the Pool contract:

// src/UniswapV3Pool.sol

function increaseObservationCardinalityNext(

uint16 observationCardinalityNext

) public {

uint16 observationCardinalityNextOld = slot0.observationCardinalityNext;

uint16 observationCardinalityNextNew = observations.grow(

observationCardinalityNextOld,

observationCardinalityNext

);

if (observationCardinalityNextNew != observationCardinalityNextOld) {

slot0.observationCardinalityNext = observationCardinalityNextNew;

emit IncreaseObservationCardinalityNext(

observationCardinalityNextOld,

observationCardinalityNextNew

);

}

}

And a new function to Oracle:

// src/lib/Oracle.sol

function grow(

Observation[65535] storage self,

uint16 current,

uint16 next

) internal returns (uint16) {

if (next <= current) return current;

for (uint16 i = current; i < next; i++) {

self[i].timestamp = 1;

}

return next;

}

In the grow function, we’re allocating new observations by setting the timestamp field of each of them to some non-zero value. Notice that self is a storage variable, assigning values to its elements will update the array counter and write the values to the contract’s storage.

Reading Observations

We’ve finally come to the trickiest part of this chapter: reading of observations. Before moving on, let’s review how observations are stored to get a better picture.

Observations are stored in a fixed-length array that can be expanded:

As we noted above, observations are expected to overflow: if a new observation doesn’t fit into the array, writing continues starting at index 0, i.e. oldest observations get overwritten:

There’s no guarantee that an observation will be stored for every block because swaps don’t happen in every block. Thus, there will be blocks that have no observations recorded, and such periods of missing observations can be long. Of course, we don’t want to have gaps in the prices reported by the oracle, and this is why we’re using time-weighted average prices (TWAP)–so we could have averaged prices in the periods where there were no observations. TWAP allows us to interpolate prices, i.e. to draw a line between two observations–each point on the line will be a price at a specific timestamp between the two observations.

So, reading observations means finding observations by timestamps and interpolating missing observations, taking into consideration that the observations array is allowed to overflow (e.g. the oldest observation can come after the most recent one in the array). Since we’re not indexing the observations by timestamps (to save gas), we’ll need to use the binary search algorithm for efficient search. But not always.

Let’s break it down into smaller steps and begin by implementing the observe function in Oracle:

function observe(

Observation[65535] storage self,

uint32 time,

uint32[] memory secondsAgos,

int24 tick,

uint16 index,

uint16 cardinality

) internal view returns (int56[] memory tickCumulatives) {

tickCumulatives = new int56[](secondsAgos.length);

for (uint256 i = 0; i < secondsAgos.length; i++) {

tickCumulatives[i] = observeSingle(

self,

time,

secondsAgos[i],

tick,

index,

cardinality

);

}

}

The function takes the current block timestamp, the list of time points we want to get prices at (secondsAgo), the current tick, the observations index, and the cardinality.

Moving to the observeSingle function:

function observeSingle(

Observation[65535] storage self,

uint32 time,

uint32 secondsAgo,

int24 tick,

uint16 index,

uint16 cardinality

) internal view returns (int56 tickCumulative) {

if (secondsAgo == 0) {

Observation memory last = self[index];

if (last.timestamp != time) last = transform(last, time, tick);

return last.tickCumulative;

}

...

}

When the most recent observation is requested (0 seconds passed), we can return it right away. If it wasn’t recorded in the current block, transform it to consider the current block and the current tick.

If an older time point is requested, we need to make several checks before switching to the binary search algorithm:

- if the requested time point is the last observation, we can return the accumulated price at the latest observation;

- if the requested time point is after the last observation, we can call

transformto find the accumulated price at this point, knowing the last observed price and the current price; - if the requested time point is before the last observation, we have to use the binary search.

Let’s go straight to the third point:

function binarySearch(

Observation[65535] storage self,

uint32 time,

uint32 target,

uint16 index,

uint16 cardinality

)

private

view

returns (Observation memory beforeOrAt, Observation memory atOrAfter)

{

...

The function takes the current block timestamp (time), the timestamp of the price point requested (target), as well as the current observations index and cardinality. It returns the range between two observations in which the requested time point is located.

To initialize the binary search algorithm, we set the boundaries:

uint256 l = (index + 1) % cardinality; // oldest observation

uint256 r = l + cardinality - 1; // newest observation

uint256 i;

Recall that the observations array is expected to overflow, that’s why we’re using the modulo operator here.

Then we spin up an infinite loop, in which we check the middle point of the range: if it’s not initialized (there’s no observation), we continue with the next point:

while (true) {

i = (l + r) / 2;

beforeOrAt = self[i % cardinality];

if (!beforeOrAt.initialized) {

l = i + 1;

continue;

}

...

If the point is initialized, we call it the left boundary of the range we want the requested time point to be included. And we’re trying to find the right boundary (atOrAfter):

...

atOrAfter = self[(i + 1) % cardinality];

bool targetAtOrAfter = lte(time, beforeOrAt.timestamp, target);

if (targetAtOrAfter && lte(time, target, atOrAfter.timestamp))

break;

...

If we’ve found the boundaries, we return them. If not, we continue our search:

...

if (!targetAtOrAfter) r = i - 1;

else l = i + 1;

}

After finding a range of observations the requested time point belongs to, we need to calculate the price at the requested time point:

// function observeSingle() {

...

uint56 observationTimeDelta = atOrAfter.timestamp -

beforeOrAt.timestamp;

uint56 targetDelta = target - beforeOrAt.timestamp;

return

beforeOrAt.tickCumulative +

((atOrAfter.tickCumulative - beforeOrAt.tickCumulative) /

int56(observationTimeDelta)) *

int56(targetDelta);

...

This is as simple as finding the average rate of change within the range and multiplying it by the number of seconds that have passed between the lower bound of the range and the time point we need. This is the interpolation we discussed earlier.

The last thing we need to implement here is a public function in the Pool contract that reads and returns observations:

// src/UniswapV3Pool.sol

function observe(uint32[] calldata secondsAgos)

public

view

returns (int56[] memory tickCumulatives)

{

return

observations.observe(

_blockTimestamp(),

secondsAgos,

slot0.tick,

slot0.observationIndex,

slot0.observationCardinality

);

}

Interpreting Observations

Let’s now see how to interpret observations.

The observe function we just added returns an array of accumulated prices, and we want to know how to convert them to actual prices. I’ll demonstrate this in a test of the observe function.

In the test, I ran multiple swaps in different directions and at different blocks:

function testObserve() public {

...

pool.increaseObservationCardinalityNext(3);

vm.warp(2);

pool.swap(address(this), false, swapAmount, sqrtP(6000), extra);

vm.warp(7);

pool.swap(address(this), true, swapAmount2, sqrtP(4000), extra);

vm.warp(20);

pool.swap(address(this), false, swapAmount, sqrtP(6000), extra);

...

vm.warpis a cheat code provided by Foundry: it forwards to a block with the specified timestamp. 2, 7, 20 – these are block timestamps.

The first swap is made at the block with timestamp 2, the second one is made at timestamp 7, and the third one is made at timestamp 20. We can then read the observations:

...

secondsAgos = new uint32[](4);

secondsAgos[0] = 0;

secondsAgos[1] = 13;

secondsAgos[2] = 17;

secondsAgos[3] = 18;

int56[] memory tickCumulatives = pool.observe(secondsAgos);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[0], 1607059);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[1], 511146);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[2], 170370);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[3], 85176);

...

- The earliest observed price is 0, which is the initial observation that’s set when the pool is deployed. However, since the cardinality was set to 3 and we made 3 swaps, it was overwritten by the last observation.

- During the first swap, tick 85176 was observed, which is the initial price of the pool–recall that the price before a swap is observed. Because the very first observation was overwritten, this is the oldest observation now.

- The next returned accumulated price is 170370, which is

85176 + 85194. The former is the previous accumulator value, the latter is the price after the first swap that was observed during the second swap. - The next returned accumulated price is 511146, which is

(511146 - 170370) / (17 - 13) = 85194, the accumulated price between the second and the third swap. - Finally, the most recent observation is 1607059, which is

(1607059 - 511146) / (20 - 7) = 84301, which is ~4581 USDC/ETH, the price after the second swap that was observed during the third swap.

Here’s an example that involves interpolation: the time points requested are not the time points of the swaps:

secondsAgos = new uint32[](5);

secondsAgos[0] = 0;

secondsAgos[1] = 5;

secondsAgos[2] = 10;

secondsAgos[3] = 15;

secondsAgos[4] = 18;

tickCumulatives = pool.observe(secondsAgos);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[0], 1607059);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[1], 1185554);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[2], 764049);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[3], 340758);

assertEq(tickCumulatives[4], 85176);

This results in prices: 4581.03, 4581.03, 4747.6, and 5008.91, which are the average prices within the requested intervals.

Here’s how to compute those values in Python:

vals = [1607059, 1185554, 764049, 340758, 85176] secs = [0, 5, 10, 15, 18] [1.0001**((vals[i] - vals[i+1]) / (secs[i+1] - secs[i])) for i in range(len(vals)-1)]